Rethinking Build vs Buy: Designing Your Product Ecosystem

How to decide what to build, what to buy, and how it all fits into one coherent product experience.

In most organisations, the question of build vs buy is handled roughly like this: you compare a few vendors, estimate some effort, line up licence costs against headcount… and then you make what looks like a rational decision.

Except over time, those “rational” decisions silently reshape your entire product ecosystem. Critical flows end up scattered across different tools. Data and logic moves outside your core product. Roadmap priorities start to follow vendor’s strategy rather than your own.

The real problem isn’t whether you buy yet another tool.

The problem is when you accidentally move parts of your core product outside your control.

That’s why I believe that

Build vs buy is not a procurement question. It’s a product strategy decision.

From “Tools” to “Ecosystem”

Let’s shift the question.

Instead of asking: “Should we build or buy this feature?”

Ask: “What does our product ecosystem look like, and where does this new capability fit?”

By product ecosystem I mean the full set of capabilities your users rely on, the end-to-end journey they experience, and the underlying systems that hold your data and decision logic.

Your goal is to create one coherent experience for your users, even if behind the scenes you assemble it from built components, bought tools, and integrations.

So before you start discussing solutions, map the user journey for your primary personas and mark the moments where users would say: “This is the product.” Treat those moments as sacred. They are prime candidates for building or deeply embedding into your core product.

Everything else is negotiable.

Principle 1 – Start From the User Journey, Not the Feature List

Most build vs buy conversations start from a feature: “We need advanced analytics / a shift-planning tool.” The problem is that features live in isolation; users don’t.

Start with the user journey instead. Where do users log in first? Which screens do they spend the most time on? Where do they make decisions that actually matter – approving, rejecting, prioritising, paying? Only then ask where the new capability fits in this flow.

A simple rule of thumb:

If users experience the feature as “the product”, lean towards building or deeply embedding it.

That doesn’t mean writing everything from scratch. It means your product owns the experience, while any external tools stay largely invisible. The user should feel like they’re using one product, not being moved out into “another system”.

Principle 2 – Differentiate vs Hygiene

Not every capability deserves the same level of attention.

Some are differentiating: they directly contribute to your unique value proposition, make your product hard to replace, and give you leverage in sales conversations. For example: a proprietary optimisation engine or domain-specific workflows.

Others are hygiene or commodity: customers expect them, but they don’t choose you because of them. Email sending, generic dashboards, ticketing – there are plenty of good vendors in these spaces, and you won’t win by building your own and then maintaining it forever.

The rule of thumb here is:

Protect your differentiation; don’t reinvent hygiene.

In reality, you’ll encounter a lot of grey areas. Something that starts as hygiene (“basic reporting”), can, over time, become a key part of your differentiation (“we provide unique and actionable insights”). That’s why you need a repeatable way to revisit earlier decisions. We’ll come back to this when we talk about governance.

Principle 3 – Decide Where the “Brain” Lives

This is the principle most teams skip.

You can plug in many tools and integrations, but you should be very intentional about two things:

where your core domain data lives (customers, contracts, orders, etc), and

where critical decisions are made (pricing, routing, approvals, etc).

If you move too much of the brain into SaaS tools, you end up with vendor lock-in that’s very hard to unwind. You will have very little flexibility when you want to change how things work.

The guideline I use is:

Own the brain, rent the limbs.

Rent generic functionality. But own the data models and logic that make your product valuable in your specific domain.

Owning the brain doesn’t always mean building everything yourself. It does mean that your product holds the source of truth for core entities, and that core decision logic lives in your services, not inside complex vendor configurations.

Principle 4 – Respect Your Operational Reality

And then there’s the real world: limited team capacity, budget constraints, time-to-market pressure.

You can’t ignore any of that. But you also shouldn’t let it dominate the conversation from the start.

What usually works well is to first decide where a capability ideally belongs in your ecosystem – core product or integrated tooling – and only then overlay reality:

Can we build this well enough in the timeframe we have?

Do we have the skills to maintain it?

What will we deprioritise on the roadmap if we build it?

If we buy, what does the vendor roadmap look like, and how much lock-in are we accepting?

Rule of thumb:

Your product strategy decides what you would do. Time, capacity, and budget adjust how and when you do it.

Sometimes you’ll consciously decide: “Ideally we would build this, but we can’t afford to right now. We’ll buy a tool and review in 12–18 months.” That’s fine – as long as it’s intentional and documented, not accidental.

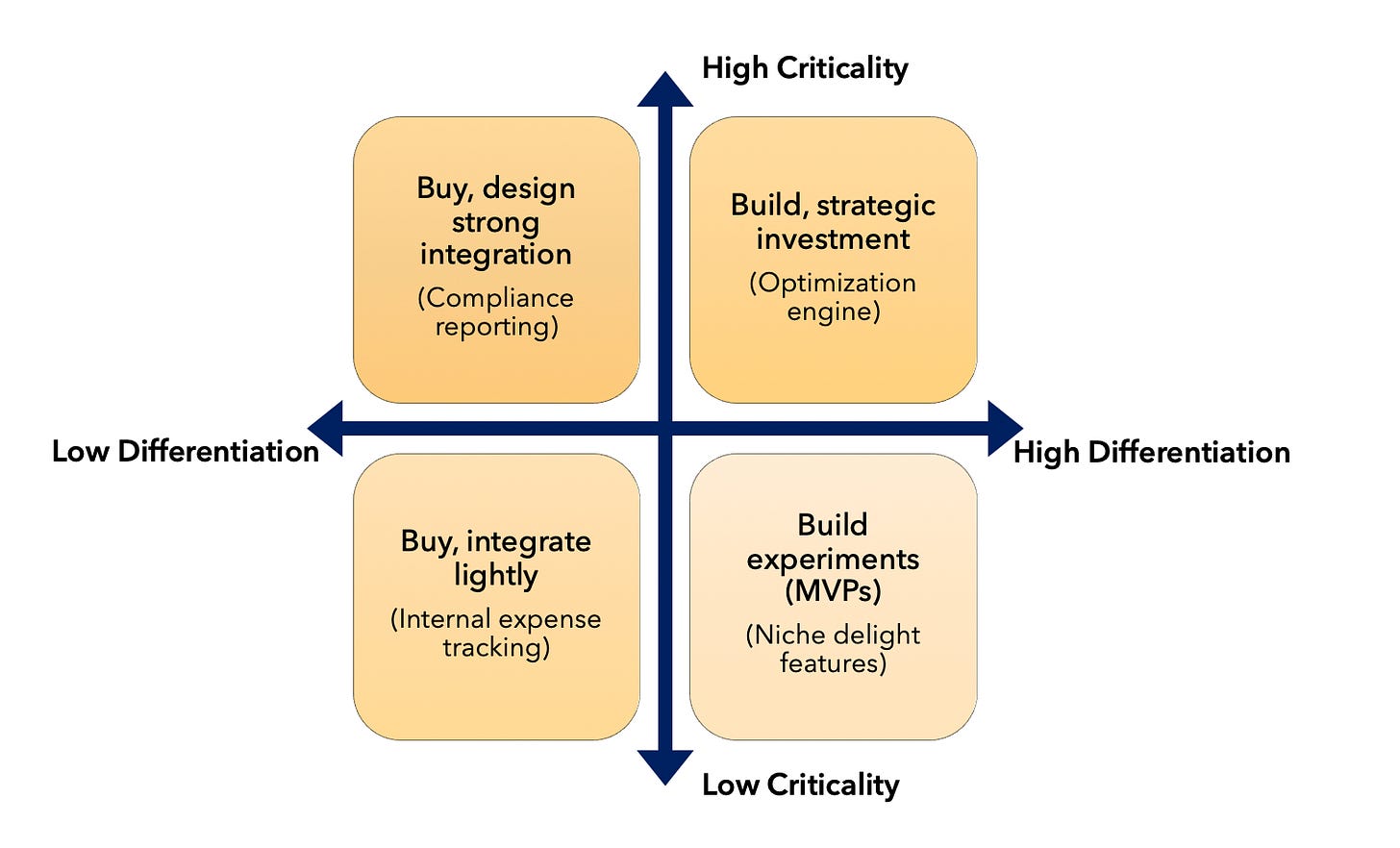

A Simple Build vs Buy Decision Matrix

Here’s a simple matrix you can use as a general guideline.

Low differentiation / Low criticality

Think about internal expense tracking for your own team. It needs to work, but it’s not why your product exists. The answer is simple: buy something off the shelf, integrate it lightly, and don’t spend more energy here.

Low differentiation / High criticality

Compliance reporting is a good example: customers don’t choose you for it, but mistakes can have serious consequences. In this quadrant you usually still buy, but you design solid data integrations and make sure you can switch tools later without risking your data or your obligations.

High differentiation / Low criticality

Here you’ll find niche features that delight a specific segment of your users. They may not be business-critical, but they can strengthen your positioning. This can be a good space to build, especially if you can iterate quickly. It’s a natural place for experiments and small MVPs.

High differentiation / High criticality

This is where your routing engine, pricing logic, or other core logic live. This is central to your value proposition and risky to outsource. You typically build and treat the capability as a strategic product investment. You want control, flexibility, and deep integration with the rest of your ecosystem.

The matrix doesn’t replace judgement, but it forces you to articulate why you’re deciding one way or another.

Example

Let’s show this on a concrete example.

Imagine FleetFox, a company that optimises last-mile delivery for retailers. Their core promise is: “We help large retailers deliver faster and cheaper, with fewer failed deliveries.”

Their core product is an optimisation engine and a dispatcher console for operations teams. The main users are retailers’ ops managers, FleetFox’s own operations team, and drivers on the road.

As FleetFox grows, they face several build vs buy decisions.

Decision 1 – Driver performance & safety score

Management wants better visibility into driver performance. They don’t just care about on-time delivery; they also want to combine customer feedback and safety signals like harsh braking or speeding.

This is at the heart of their value proposition: reliable delivery, fewer incidents, a better experience for the retailer’s customers. If they get this right, it can become a clear differentiator: “We don’t just ship parcels; we help you improve your fleet.”

The “brain” here lives inside FleetFox. Delivery outcomes, telematics data, and complaints are all core domain events. They form a unique picture of performance that generic tools don’t understand out of the box.

So they decide to build this capability as part of the core product, and, where useful, buy specific components under the hood. “Driver performance and safety score” becomes a first-class concept in the FleetFox product, not just a metric that is part of someone else’s dashboard.

Decision 2 – Incident reporting & ticketing

Next, retailers ask for a better way to report incidents like damaged packages or missing shipments. They want to log a case and see it’s progress through to resolution.

This matters, but it’s not the core differentiator of the product. Every logistics provider needs some form of incident management; very few are chosen specifically because of it. This fits in the category High criticality/Low Differentiation.

Incidents do need to connect back to FleetFox’s core entities – shipments, routes, drivers – but the basic ticketing flow is commodity.

The team is already stretched on the optimisation roadmap, and there are plenty of mature ticketing products with good APIs. FleetFox therefore decides to buy a ticketing tool and build only a thin integration layer:

Retailers create and view incidents inside the FleetFox UI.

Behind the scenes, incidents are synced to the ticketing system.

Core data about shipments and routes continues to live in FleetFox.

To the retailer, it feels like one product. To FleetFox, it’s implemented via a bought tool.

Decision 3 – Internal shift-planning tool

Finally, FleetFox’s own operations team needs a way to plan driver shifts better. This is an important internal problem, but retailers never see it.

From a product strategy perspective, this clearly sits on the “low differentiation” side. Good shift planning helps FleetFox run efficiently, but nobody buys FleetFox because of the internal tool. Some constraints and data points need to come from the core system, but overall this is an internal process problem, not a core product capability.

On top of that, there is zero capacity to build and maintain a custom internal planner, and the market is full of tools that already solve this well.

So FleetFox chooses to buy an off-the-shelf planning tool and integrate it lightly: export/import, maybe a few data syncs and no complex deep integration. They’ll only revisit this decision if their scale or complexity increases to the point where it starts touching the core value proposition.

Making Decisions Stick

You do not need a large governance structure for every build vs buy question, but it helps to have some structure to make decisions consistent and traceable.

A useful first step is to define and document a small set of principles. For example: distinguish between differentiation and hygiene; own the brain, rent the limbs, etc. When these principles are written down and shared, discussions and decisions flow easier.

For more significant decisions, it is worth using a single-page decision note. This should briefly describe the problem and user journey, indicate where the capability sits in your ecosystem, position it on the differentiation/criticality matrix, summarise the options considered, outline key risks such as lock-in or maintenance, and state the final decision with a next review date. The goal is clarity. Someone joining later should be able to understand why the decision was made.

It is also important to know who participates in the decision. Typically, Product represents the customer problem and value, Technology is responsible for architecture and feasibility, Finance covers cost and contractual aspects, and the relevant business stakeholder brings the business perspective. In most cases, this is sufficient.

Common Anti-Patterns

There are a few common anti-patterns that I find worth mentioning.

The tool sprawl. Different teams adopt their own tools independently, and you end up with multiple logins, overlapping functionality, and a fragmented experience for both customers and internal users.

“We can build anything” syndrome. Teams are confident in their ability to build and gradually recreate commodity capabilities that could have been purchased. Over time, this translates into a heavy maintenance burden and less capacity for valuable differentiating work.

Vendor as product. Core flows migrate into a SaaS platform, and your own product becomes a thin layer around it. You lose flexibility and power because key decisions and data structures effectively live in someone else’s system.

Silent lock-in. Dependence on a vendor becomes visible only when you attempt to switch and discover that migration is complex, expensive, or simply not feasible with the current setup.

Be aware of these anti-patterns. This will make it easier to recognise when a seemingly harmless decision is moving you towards an undesired direction.

Before Your Next Decision

For your next build vs buy discussion, start with a short set of questions:

User journey. Will users experience this as “the product” or as a background function?

Differentiation. Does this capability meaningfully support how we win or stand out in the market?

Brain vs limbs. Does it touch core domain data or decision logic we must own and control?

Criticality. What is the impact if this fails or is unavailable for a day? For a week?

Time and capacity. Can we build and maintain this without derailing more important roadmap work?

Vendor risk. If we buy, how easy is it to export data and switch later? Does the vendor’s roadmap align with where we want to go?

Review horizon. Are we making a permanent decision, or a 12–18 month bridge solution that we plan to revisit?

Capture the answers on a single page and use them when later you revisit the decision.

Build vs buy is not only about saving money or shipping faster. It is how you design your product ecosystem: deciding what you own, what you rent, and how it all comes together into a coherent experience for your users.

Enjoyed this read? Subscribe to Lean Product Growth for regular updates on building and scaling a successful product organization.